- Home

- Rory B. Byrne

The Fairy Mound Page 5

The Fairy Mound Read online

Page 5

There was a bustling outside. Niall opened the door and motioned me outside. I saw six strappingly tall Highlanders waiting for me to emerge from the stone jail. I saw women of the hamlet chattering between them and laughing. In the face of everything, I thought if I was to leave that place, dead or alive, I was going to do so with dignity.

Clansmen stood around their chieftain. Fiona slipped out from behind her father. She had a handful of sticks with one perched in her mouth. She chewed on it and ran it over her teeth. Without fear, Fiona walked up to me and handed me the fistful of stalks.

The reed in her mouth came out. “Want me to show you?” she asked. I saw the chewed end and tooth marks down its shaft.

“I think I can work it out,” I said.

I put one in my mouth. I ignored people watching me trying to use the reed like a toothbrush. I nibbled on the hard stalk. It had an unexpected effect on my mouth. I felt my taste buds respond to the natural chemicals in the reed. My mouth felt refreshed. The teeth lost the buildup from not brushing.

Then I saw that people had stopped paying attention to me. They went back to eating breakfast and passing flasks. A few shared mugs and swapped stories. I wasn’t as exciting a topic in the morning as I was the day before.

I noticed the distinct separation of the sexes. Women gathered, chattered, and had domestic chores like cooking. I saw a few making grass weaves, and some worked on fabrics. The men were hunters, the bringers of fortune and life within the clan. I considered that although they didn’t necessarily practice women’s rights, I knew I likely wouldn’t have lived as long if I had been a male here with my identity in question.

I didn’t know much about cultural anthropology. I knew it was a patriarchal society. The class stratum wasn’t easy to read. They were protective but not openly affectionate.

Women tended cooking fires, collected grease from the meat that dripped into leather pouches. They weren’t wasteful people. I noticed there was a purpose to their bustling. They stacked furs on flat carts. I saw a few goats among the sheep. I saw people gathering items as if getting ready for something to happen.

I saw Deirdre marching toward me from a group of women. Another woman walked with her. They stared at me, and I felt they meant harm. I readied myself for anything. I didn’t see Alasdair, but Fiona seemed indifferent to their approach.

Then Deirdre tossed a garment at me. It had swirls of green and blue. It smelled like smoke, and I couldn’t make the shape.

“We made this for you,” Deirdre said. “Elspeth said you needed a cloak.”

“You cannot stay in the wild with no cloak,” Elspeth said.

“Thank you,” I said. I pulled the wrap away from my chest to make sense of its shape.

“Dah,” Deirdre grunted.

She stepped forward and yanked the fabric from my hands. It took little time for her to throw it over my shoulders. It draped down my front and covered me entirely to my knees.

Fiona had a braided belt made of hemp that went around my waist. It drew in the fabric, and I suddenly looked like everyone else. Except my ‘cloak’ didn’t have the same tartan as Clan Slora.

“Thank you,” I said again.

Deirdre turned and left me standing beside Fiona.

“Is she always like that?” I asked.

“It suits her,” the girl said. Fiona ran off after the women. She spun around, lifting her hand. “Bye, Harper.”

“Uh, bye,” I said.

It felt like finality. They were leaving the hamlet. I understood their movements and the gathering of supplies. Some clansmen began herding the sheep and goats from the hillsides. Niall and Devlin stopped monitoring me. They moved off to join the other Highlanders. The clan left me alone. It was a bizarre farewell.

Then I saw Alasdair. He wandered through the busy people and stepped in front of me.

“Laomann bids you well,” he said. “Clan Slora thanks you for helping Fiona.” He let the words drop, unable to go on.

“I’m sorry if I did anything wrong,” I said. I didn’t know how else to respond. “I’m not going with you,” I added crestfallen.

“Aye,” he said. “They worry for you. I think Niall convinced most you are a Glaistig.” He shook his head. “I cannot change their minds. I think it is foolish.” He rubbed his neck. The thick black locks cascaded over his shoulders. “I hope you find your clan, Harper.”

He turned from me. When Alasdair got a few meters from me, he stopped. I waited, holding my breath. I felt like an abandoned child. My hands trembled. Morning brought clear skies to the east. The hammering of my heart increased. He turned back to me.

When he stepped in front of me again, Alasdair removed something from the folds of his wrap. It was a narrow tube of carved wood. He held it out to me.

“This was my mother’s,” he said. “I think it will serve you better than me.” He placed the object in the palm of my hand. I felt his course fingers scrape against my hand. His eyes lingered on me. I felt the chill of loneliness before he even left. “Goodbye, Harper of Clan Biel.”

“Bye, Alasdair.”

He gave me a few lingering glances as he walked away again. He lifted his right hand in a final wave. Alasdair joined his clansmen, and they moved off in groups, following the hillside gravel that led away from the area. I heard cheerful banter in the distance, mingling with laughter, and someone started singing a strange song.

I looked down at my front. My muddy boot tips poked out below the cloak. “What in the world is a Glaistig?” I whispered.

I examined the thing Alasdair had handed me. The hard shell sheath had ornate carvings in the rosewood. The handle matched the cover with perfect symmetry. It was delicate and beautiful. It didn’t have a pommel, just the handle and sheath. The blade was black and had imperfections on the hammered metal. The knife felt solid and was maybe eight centimeters long from end to end. It was a parting gift, and they had left me standing in their abandoned hamlet.

Ghillie Dhu

I snuffed out any negative thoughts that crawled across my back. I poked the bandages on my wrist. There wasn’t any pain, and the heat from infection had subsided. The balm Ainslie had applied to the scratch had done the trick. I pulled at the bandage to get a look at part of the wound. The concoction dried to a crusty black, coating the scratches thoroughly.

“What’s going on?” I shouted. I heard meek echoes from the wet hills.

Frustration made me angry. Clan Slora abandoned me and their hovels. Whatever they left behind, I assumed I’d make use of.

Systematically, I explored each of the huts. They were little more than stone tents against the elements. The hardened mud and stone withstood the cold winds. Wearily, I listened for raiders. I worried the rogue clansmen might return for more snacks, including me, as a prize.

I stood among the empty huts.

“What am I supposed to do?”

The clan had departed shortly after daybreak. I had all day to decide my next move. I had found civilization in the new—old Scotland. And civilization didn’t want me.

Sunset brought cold winds and drizzle. I managed to scrape together enough kindling to reignite the leftover fire inside the hut where I first awoke. Since it had a fireplace, I thought it was better to die hungry and warm instead of freezing and starving.

“I’m along again, I’m miserable, and I’m hungry.”

I wasn’t much for talking to myself. Back in the real world, people talking to themselves usually had some mental issues. I felt if I at least had some psychological problems, I might not feel so alone and scared.

I did score during my search through the huts. I found a deerskin flask. At least I wouldn’t get thirsty while I starved to death. It had a woven hemp strap that was long enough to drape over my shoulder like a purse strap. And it still held water.

I settled into the hut with the

fireplace, managed to collect enough damp twigs and bracken to keep the fire going all night, hopefully.

When the sun fell out of the sky, raindrops smacked at the thatch overhead. Surprisingly, the weave of sticks and Highland grass didn’t leak. The night brought the fantasies of returning marauders and made it impossible to sleep. Instead, I used the quiet to organize and rationalize my predicament.

“I’m somewhere in Scotland.” It was a fact. The topography and the indigenous people made it abundantly clear. “I don’t know how or why, but I’m somewhere back in time. I think this had something to do with Mom’s research. Those people at Equinox Technologies found a portal, or a wormhole, something to make Einstein and Hawking proud.”

Thinking of my mother and her work made me consider alternative history.

“I’m a disruption in the timeline,” I said. “Something to do with a grandfather paradox, something about how the past had significant consequences for the future,” I added. “See, Mom? I was listening!”

I sighed.

“Don’t step on any butterflies.” I looked at the thatched door from the safety of my corner in the hut. “If I’m in the past now, then everything is already different in the future.” I remembered watching some of Mom’s lectures online. She wasn’t much for time travel trivia. But people connected quantum entanglement to traveling through time. Cause and effect were simple terms with huge ramifications.

“Everything I’ve done since I got here has already impacted the future.” I thought about my place in the new—old world. “I am a stranger in a strange time.”

I propped in the corner of the shelter. With the deerskin wrapped around my shoulders, I held the sheathed dagger in my fist.

“Thank you for the knife, Alasdair,” I said. “Oh, and by the way, you are a knockout. I should have said that to him. Would it have made a difference?”

Daybreak came, and I smelled something sweet in the air. I woke with a start to the gloom of the hut. The fire had died in the night. Sunlight clawed at the thatch overhead. I survived another night.

I sniffed the water in the flask before taking a sip. I didn’t want to think of how many lips the deerskin had touched before it reached me. At this point, cooties were the least of my worries.

I wanted to wash my face. I set out a few stone bowls the clan left behind, hoping to collect rainwater overnight. When I peeked out, scanning the other shelters, I saw my bowls, but one of the sheds on the other end of the campsite had smoke trailing out of its thin chimney.

Since it was the chieftain’s shelter, I figured it wasn’t for someone ordinary like me. Of course, I looked around inside. The clansmen left a collection of old rags that I thought I’d take in a pinch if I needed more warmth or something to burn later.

I made my way through the alleyway between the stone sheds to the one at the far end. I knew there wasn’t fire there the night before, and if the clansmen had returned in the night, they hadn’t made any noise. I felt my heart in my throat at the thought of it being the raiders who had come back to pick over things, but at least I’d face the menace head-on.

I didn’t rush into the chieftain’s hut. Instead, I took baby steps until I pulled at the door. The gloom inside made it hard to see details. I smelled raw earth but also the aroma of something sweet cooking on the hearth inside.

Undoubtedly, I wasn’t alone. Sometime in the night, someone had occupied the hut only a few doors down from where I slept. Perhaps the hamlet was nothing more than a Highland motel for transients.

I saw the pile of fabric rags in the corner at an arm’s length from the tiny fireplace. I saw a small fire and a pot hanging from a spit over the flames.

With the door wide open, allowing as much sunlight into the place as possible, I stepped farther into the shelter. It wasn’t like there was any place to hide. It was four walls, a roof and a door, plus the fireplace. The fabric in the corner lay in a mound. The material looked more like woven grass than real fabric. When the pile stirred, I felt my skin prickle with goosebumps. I sucked in a quick breath and bit my tongue to keep from squealing in fright.

The shape moved, and the mound of mottled fabrics rose as if something stirred inside. I saw the face of an older man appear within the folds of earthy fabric. He had a hook nose, bushy white eyebrows that matched the overgrown beard, and gray eyes that gathered the light in the space. The material gathered over his frail shoulders like a cloak.

“Oh,” I said. The sudden appearance of an elder wasn’t something I saw every day. Of course, everything had changed, so I shouldn’t have been so surprised. “I didn’t know anyone was still here.”

I considered perhaps it was intentional, ritualistic abandonment for the feeble or infirmed.

“Th’ bairns hae a’ gaen awa,’”

“Yeah, sorry, I don’t speak Gaelic. I’m just passing through. I didn’t mean to disturb you.”

As the words came out of my mouth, my stomach decided to speak up. It growled angrily at the idea I missed out on filling it with something more nutritious than stale rainwater from a flask.

His eyes went to my wrist. The dirt rags over the wound frayed and had unwound some through the night. The old man managed to sit up. He remained fixed to the sod floor, nestled within the heap of cloth that looked grown from the earth. The gaunt face remained passive, almost pleasant under the great wooly eyebrows.

Pale and fragile fingers reached out from under the material around him. His fingers were bony and long, and the nails were caked with dirt. His wrists were emaciated with pronounced ulnas under taut, paper-thin skin. He pointed to the bandage.

“Cat attack,” I said. The chuckle from my throat was a way to ease my tension.

He barely moved. He was disturbingly still, as if part of the floor and the fabric. I didn’t see any more of him than the face and one arm motioning to my right hand. His fingers waggled at me to come closer.

I took another step toward him. I didn’t know if he wanted to see my hand or needed me to help him stand up. I offered my left hand. His fingers were shockingly cold, as if he had crawled from the ground. But he was surprisingly strong. I pulled lightly, letting him do all the work while I played the anchor.

The old man didn’t exactly stand up as much as rose off the ground, still shrouded in the mossy fabric. He was no taller than me and thinner even. His face was a fleshy bag of soft wrinkles. When he smiled, his teeth were long and tarnished, but he had most of them still in his head. I noticed that before with the clansmen. The reeds were substitutes for a toothbrush. Very few of the clansmen had bad teeth that I saw.

“I’m Harper Biel,” I said. “I don’t think you can understand me. I wish I could understand you.” I smiled for him to show I was harmless. I hoped the same for him. “I guess I’m thankful for the company. Maybe you’ll understand when we starve to death together.”

“If you listen, you will know,” he said.

“Oh, well, good, I got that,” I said. “Can I have my hand back, please?” He didn’t let go.

“Harper,” he said.

“Yes, that’s me.” I gave him a sickly laugh because he had boundary issues, smelled like wet earth, and managed to stand as still as a statue. “I feel like, if you let go, I’ll stick around long enough for you to bestow some divine wisdom on me. Is that a deal?”

His eyes drifted lazily over me. It wasn’t lurid, and he focused on my right hand again. That’s when his other hand closed around my right arm. It startled me. I didn’t see him reach for it. I felt him grip my wounded arm. He bent closer, and before I could stop him, the bandages dropped to the floor.

“Ainslie, I think, is the clan healer. She put that smelly black stuff on my arm. I don’t know if it did any good, but at least it doesn’t hurt as much. Maybe the arm will fall off before it poisons me.”

The old man used his thumb to break off the flaky paste

covering the deep scratches. I saw the pus and crust. It stopped hurting because the flesh had started decaying.

“That doesn’t look good. I should go wash it. Maybe pour boiling water on it. If you let go, I—”

Both hands cupped my arm. I couldn’t move. While I knew it was impossible, I saw the cloak he wore moved over my hand, and it moved up my arm. I felt the tingling immediately. I was as if a thousand tiny spiders tap-danced on my scratches. I saw him concentrating, and with his eyes closed, he sighed. His breath smelled like wet soil. It wasn’t pungent, just different.

“If you listen,” he whispered. His words were slow and deliberate. “You will understand.”

When the fabric pulled free of my wrist, the wounds had vanished.

Lack of calories made me lightheaded. I felt dizzy by the idea that something this profound had happened.

“I feel weird,” I said.

Before I tipped sideways, the old man’s arms and the mossy cloak caught me. He lowered me to the ground like a deflated balloon, managing to keep me from knocking my head.

“You feel the healing,” he said. I found it challenging to keep my eyes open.

Travelers

The sweetly scented porridge tasted like creamy oats. I don’t know where he got it. I don’t know how he made it. But I was thankful for the steaming bowl. I used my fingers to scoop it into my mouth and then wiped my face on the sleeve of my jacket. He appeared pleased with my lack of girly manners.

“You are better now,” he said.

I lifted my right arm, as if it needed clarification.

“I feel a lot better. I don’t know how you did it. I appreciate it. Can I ask your name?”

“Call me, Ghillie Dhu.”

“Thank you, Gilly Do,” I said.

“You are most welcome, Harper of Clan Biel.” He was level with me, sitting on the floor. I didn’t see the rest of him. Other than the bearded face, and the occasional hand from the folds of fabric, the rest of him was a mystery.

The Fairy Mound

The Fairy Mound The White Witch

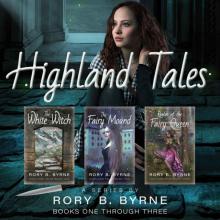

The White Witch Highland Tales Series Box Set

Highland Tales Series Box Set